The 5 biggest mistakes writers make when turning their books into comics

Comics are a popular way for authors to expand their platform, but the majority I talk to run into the same stumbling blocks. What if you could just...not do that, though?

A ton of authors want to turn their books into comics, but they are almost all doing it wrong, costing them thousands of dollars and wasting tons of their time. This article will hopefully help you avoid to costliest mistakes I see writers make when creating their comics.

You can read almost all the comics I used in this article for free as a paid member, including Ichabod Jones: Monster Hunter, the seminal comics work of my career.

If you are a paid member, I recommend reading this article summarizing my best Kickstarter tips, this article about what to look for in a publishing contract, and this one about how to build a world-class network.

I also have a free podcast featuring interviews with comic creators David Pepose, Marv Wolfman, Jim Zub, Ben Templesmith, and Pat Shand, comic book publishers Michael Son and Barbra Dillon, and Margot Atwell, previous Director of Comics and Publishing at Kickstarter.

If you are not a paid member, you can read everything with a 7-day free trial, or give us a one-time tip.

One of the things I’ve been most successful at in my fiction career is translating novels to comics and comics to novels. For years, I considered this transmedia, but I was wrong.

Transmedia storytelling (also known as transmedia narrative or multiplatform storytelling) is the technique of telling a single story or story experience across multiple platforms and formats using current digital technologies.

From a production standpoint, transmedia storytelling involves creating content that engages an audience using various techniques to permeate their daily lives. In order to achieve this engagement, a transmedia production will develop stories across multiple forms of media in order to deliver unique pieces of content in each channel. Importantly, these pieces of content are not only linked together (overtly or subtly), but are in narrative synchronization with each other.

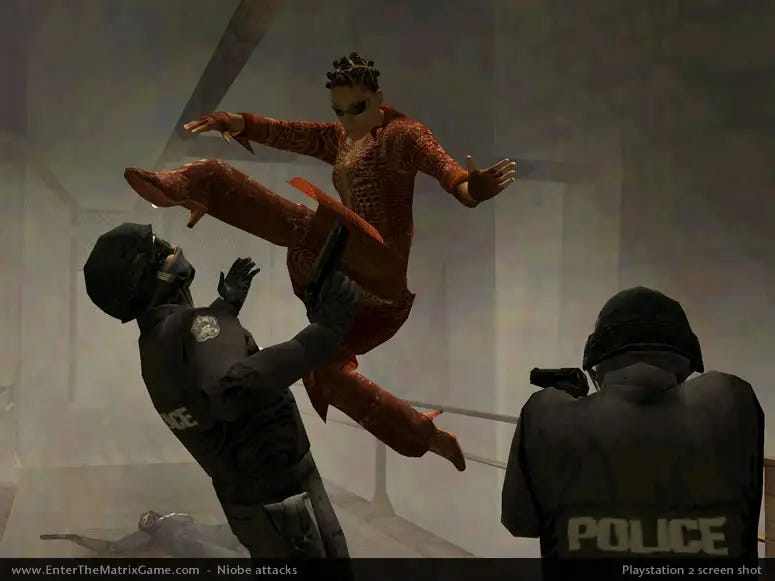

My current understanding of transmedia is that it involves telling a cohesive story across mediums. One of my favorite examples is Matrix: Reloaded.

Now, I love Matrix: Reloaded despite all the hate it receives, but I will admit that a lot of my love for that movie comes from the excellent Enter the Matrix video game. You learn so much about the world by playing the game, which is what makes it transmedia. Honestly, go play the game and then watch the movie again. It makes the movie so much better.

Another great example is The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, where the Youtube series was augmented by Twitter Feeds and other media that flushed out the world.

Instead, transitioning a comic to a book, or vice versa, is closer to translating a book into another language than transmedia.

If someone asked me to describe my relationship to literary translation, my full-time occupation for the last decade, I might call it an ungrudging obsession. It’s often difficult, occasionally all-consuming, but not without its pleasures — some of which are akin to those of the daily crossword.

Much like a crossword, a translation isn’t finished until all the answers are present and correct, with each conditioning the others. But when it comes to literature, there is rarely ever just one solution, and my job is to test as many as possible. A word can be a perfect fit until something I try in the next clause introduces a clumsy repetition or infelicitous echo. Meaning, connotation and subtext all matter, but so does style.

Below are two attempts to show the thought processes involved in the kind of translation I do. -Sophie Hughes

In the same way, transitioning a project from one medium to another is about translating the meaning, connotation, subtext, and style in a manner that would be most appealing to a new audience.

In the case of comics, instead of the new audience being readers in another language, it’s about translation into the language of how another medium works. I’m not going to show you how to understand or make a comic in that article. Scott McCloud already did it better than I ever could with Understanding Comics and Making Comics.

If you are thinking about making comics and haven’t read those two books, I would highly suggest you add them to your queue right now.

Instead, what I thought I would do is talk about the biggest mistakes authors make when translating their work into comics (aside from not reading those two books I mentioned).

Don’t get me wrong, there is a ton that comic creators have to learn about novels, but in general, those are problems of time and not money. The craft of novels is mostly learned by writing a bunch of novels and that doesn’t take a lot of money to do.

You can’t just jump into writing a novel with both feet without actually writing a book. Whereas, authors love to jump headfirst into comics, spend a bunch of money on an artist, and end up with a subpar product at the end of the day.

You can drop a ton of money in comics and make irreparable mistakes that cost tons of money to repair. I’ll likely write an article about translating comics to novels at some point, but this feels like a dire need kind of situation, so I’m focusing on going from novels to comics first.

I have watched writers make $10,000-$20,000 mistakes with their comic books. Worse, the books end up ranging from passable to embarrassing. It’s one thing to blow a wad of money and create something exceptional. It’s quite another to waste a ton of money on something unusable.

These are the mistakes I’m going to try to prevent today in this article. I’m not one to tout my bonafide, but since I don’t talk about comic craft much, you can see a complete collection of my comic work here.

I’ve produced over 1,000 pages of comics, drawn two comics, and edited four anthologies. I’ve been a comic book publisher since 2014. While we don’t put out a ton of titles a year, we have been operating profitably for nearly a decade, which is something. Most of the art I use in this article is from our books.

Paid members can read most of my personal comic book work for free. You can become a paid member with a seven-day trial.

***This is a long post that will be truncated in emails. I highly recommend you go to this page to read the whole 7,500-word post without interruption.***

Mistake #1: Not hiring an editor

The biggest mistake writers make when trying to make comics is to not hire an editor first. You might be saying “But Russell, I’ve already had my book edited. Why would I need a comics editor?”

Well, do you want to find a good artist who will actually finish your book? Do you have any aspirations about finding a publisher? Do you want to match the right artist with your work so that it reaches the right audience?

On top of all the other things that editors can do to get your script right, the right editor can cut dozens of hours and curb costly mistakes before you make them. They will probably tell you everything in this article without the snarky tone, too.

A good editor will walk you through the translation process. I mean, you would never translate a book without hiring an editor, right? Oh god, you would, wouldn’t you?

Okay, let’s go back.

Never translate a book without getting a native language editor. That’s the first rule of translation. In the same way, you want to hire somebody who can speak the language of comics.

For instance, did you know the most important part of comics is what you don’t show? The key to a good comic is getting the reader to fill in what’s happening between the panels, in the gutter.

The gutter is the space between two panels within a comic strip or comic book. At its simplest form, the gutter is a blank space that separates two panels. This blank space creates a transition from one moment to the next within a story. As comic book scholar Scott McCloud explains, the gutter is used to “take two separate images and transform them into a single idea” (McCloud, 1993, p. 66).

This statement by McCloud illustrates the concept of closure that the gutter allows. While a reader cannot see what is happening within the gutter, assumptions can be made that something happened between the panels that allow for those panels to be related in some way. -Comic Book Glossary

No, you probably didn’t, because you don’t speak comic. In comics, you should never get your mind out of the gutter. Most authors try to write every word of their script into their book, which is the cardinal sin of comics, unless you’re Alan Moore or Brian Michael Bendis.

Don’t know who those are?

No?

That’s why you need an editor. Also, go read some comics. It blows my mind how many authors want to make comics and who haven’t read comics.

Did you know that Comics Experience curates an extensive archive of comic book scripts, or that one of the best ways to learn comics is to download the script and then track down the issue to see how they compare to each other?

Of course not. Why would you? You don’t speak comics. You haven’t lived in the industry. You don’t know which companies are good collaborations and which ones stiff their creators. You don’t know any editors, but a good editor knows all of them and can open doors for you. That’s not a guarantee that they can, but they might if they resonate with the book and it turns out well.

I don’t even work as a freelance editor, but I know almost all the publishers, at least in indie comics, and most of the executive editors, at least in passing, simply by being around comics for almost 15 years. The right editor has a lot more than even me.

So, now that I’ve convinced you to hire an editor, where do you find one? Well, interestingly enough, the best editors are hiding in plain sight. You see, comics is a freelance industry, and most editors for major companies work freelance.

So, the best way to find an editor (and an artist BTW) is to head into a comic shop, buy a ton of comics, and find the ones who are doing work that resonates with you and/or is in the style of your book.

(PRO TIP: Don’t work on a book where the art style doesn’t resonate with you, and you can assume that the popular comics in a genre are a good representation of what art styles sell in that genre.)

Once you have a list of editors, go find them online and ask if they are open to work. No, they won’t work for free. However, you will be surprised to see how far you can get if you ask their rate and then pay it. Money is the secret key to the whole industry.

Even if they aren’t taking on work right now, they’ll likely either schedule you in the future or send you in the direction of somebody they recommend. The kind of work you’re asking an editor to do is usually developmental editing.

Developmental editing is a phase in the book publishing process where editors work with authors to resolve “big picture” issues in their manuscripts, including structure, form, plot, and character. Because of its focus on wider story elements, this type of editing normally won't address sentence-level errors such as punctuation and grammar typos.

Good developmental editing will bear your target audience in mind and assess your work in relation to industry standards and expectations. -Reedsy

Yes, you have already written the book, but often that makes it even more complicated for an editor than making something from scratch because you’re already attached to it. The main job of a translation editor is to get you to stop being such a whiny baby about every word you wrote like it was handed down from Heaven.

Here’s the main thing with comics: If you wait until you have a comic to hire an editor, it’s too late. No editor can fix a crappy comic that’s already been made unless you want to burn it all down and start from scratch.

Rarely, you might have a coloring or lettering problem that can be fixed easily, but if you have coloring and lettering problems, you almost always have structural art problems that you missed in the pencils or inks.

Don’t be cheap. Hire an editor.

Mistake #2: Hiring an artist that has never done comics

The main reason you need to hire somebody who has done comics is this: comics are both one of the hardest kinds of art to get right and the one that pays the worst.

Any comics artist worth their salt would probably make way more doing any other type of art. In order to stick around the comic industry, you have to love comics. If you’ve never made a comic, how will you know if you love comics enough to suffer for it?

And yes, comic artists suffer for the art more than any kind of artist. The work is tedious, the pay is low, and the rewards are paltry. We make comics because we can’t not make comics.

In order to make the same on a $5,000 book launch, I need to make at least $22,000 on a graphic novel launch…and there is no market for indie comics beyond Kickstarter.

Authors can put their books on Amazon after a Kickstarter launch and make a living, but unless an indie comic creator is willing to lug their books to conventions, there is almost no after-market for comics. We basically make all the money we will ever make on Kickstarter.

Yes, you can find a publisher, but no matter how bad a deal you get from a book publisher, it’s probably better than any deal you get in comics. Most indie publishers expect you to have not only made the comic but also funded it. They usually expect ownership of the property even if the book doesn’t sell. On the whole, comic book publishing contracts are a joke.

Sure you want to do this? Well, then. Let’s talk about why you need to hire an artist that has made comics before. These are just some of the things a great comic artist needs to consider.

Characters designed not to be gawked at once, but to be drawn hundreds of times

One of the main reasons animators make great comic artists is that they already know one of the keys of comics: It’s not what you can draw, it’s what you can replicate.

Drawing a single compelling image is nearly impossible, but a comic artist needs to replicate characters and keep them from veering off their model sheet, somewhere between 4-6 times a page.

In animation, a model sheet, also known as a character board, character sheet, character study or simply a study, is a document used to help standardize the appearance, poses, and gestures of an animated character. Model sheets are required when large numbers of artists are involved in the production of an animated film to help maintain continuity in characters from scene to scene, as one animator may only do one shot out of the several hundred that are required to complete an animated feature film. A character not drawn according to the production's standardized model is referred to as off-model. -Art with Nelson

This is some of the hardest work to do in all of art, as my passing acquaintance, Dwayne McDuffie award-winning creator, Nilah Magruder explains.

So, one thing I’ve grown to appreciate since starting a comic is it’s really, REALLY easy to go off-model. Most (all?) sequential artists and animators know this. And now I’m gonna try to talk about it ahahahaha *sobs*

So when I say consistency (for the purposes of this post anyway), I’m talking about drawing your characters over and over and having them look the same. No matter the composition, they should be recognizable and look like they belong in the same world every time you draw them.

The short answer to this is to draw draw draw. It’s really about being familiar with your designs, and the only way to get familiar with them is to draw them a lot. But that’s pretty abstract advice, so we’re going to look at various systems for learning consistency. -Nilah Magruder

If somebody hasn’t done extensive work with character design, they likely won’t be thinking like a comic artist when they design the character. Yes, you can hire a character designer, but it’s almost always easier to have your artist do it so the style stays consistent.

Characters are the basic unit of comic book art, so if you get them wrong you are setting yourself up for failure.

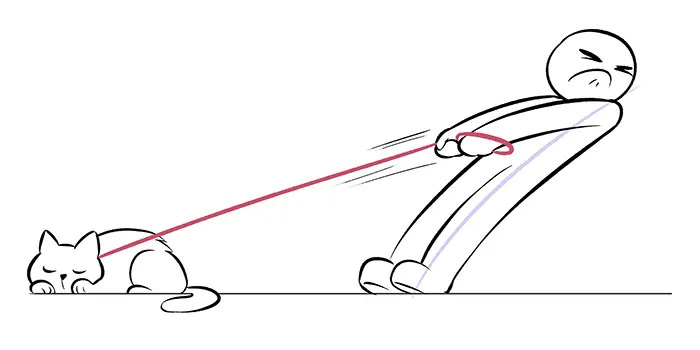

Leading lines lead to dynamic posing and expressions

It’s hard enough to create compelling leading lines in a single image, let alone a whole page of comics, let alone use them consistently to make the whole book feel like a singular expression.

Leading lines are lines in a photograph that have been framed and positioned by the photographer to direct the viewer’s attention to a particular point of focus. These lines frequently guide the viewer’s attention in a specific direction or to a specific area of the shot. -NFI

Look at how interesting that pose is above. The line of the leash guides the eye to the character on the right, and they are leaning back making it very dynamic. Dynamic poses are everything in comics.

A dynamic pose is one that depicts movement in the subject. Rather than a still, static figure, a dynamically posed drawing will portray a body in motion: leaping, dancing, running. Whether you want to draw character art, anime, manga, or just want to get better at sketches of the human body, you can hone new skills by drawing poses that leap off the page. -Adobe

It’s hard enough to do one dynamic pose in an illustration, but comics artists have to use them on every panel of every page. Not only that, but the posing has to work with the leading lines to draw the eye through the page.

Most artists can’t do that. Most artists don’t want to do it, because it’s tedious. It’s much more fun to make one impactful image. You can pull up a hundred Webtoons right now (even successful ones) where the art is boring and listless because the artists use flat poses instead of dynamic ones.

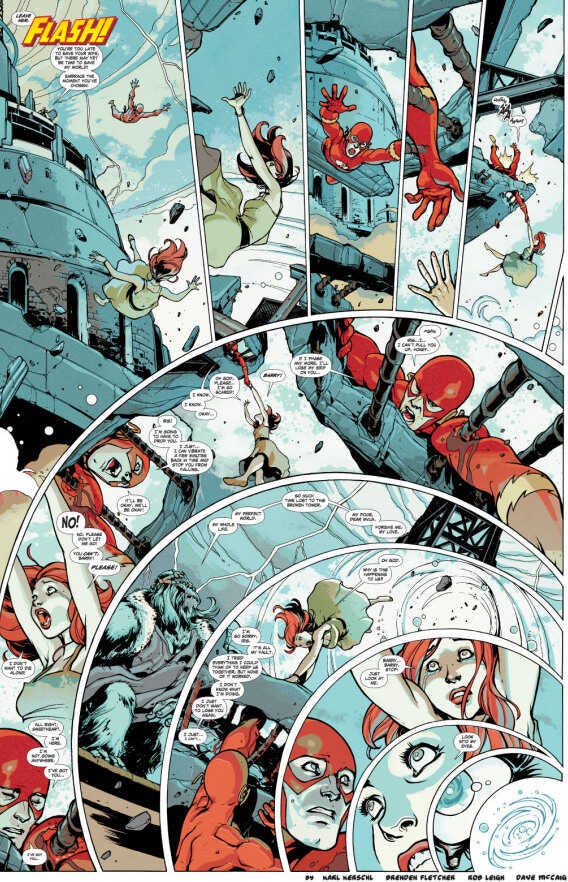

Interesting panel flow and eye lines make a comic

Look at this very simple page of comics.

Not much happens, but do you see how every angle is different, how they emphasize different areas of the page, and how the eye line leads you left to right and then back again down the page? Do you see how the space between the panels does as much work as the panels to convey movement?

Until recently there was no science to this just theory that I knew about. But in 2013 I read of a formal study done on panel layouts, and we can now say with some certainty how people are likely to read one based on a few kinds of page designs. That’s invaluable insight to add to the old wisdom, and I detail some other notions here that are borrowed for some other disciplines.

First some basics. In northamerica and the western world, we typically read comics the same way as we do pages of text. Left to right, in horizontal rows top to bottom.

Manga, Japanese Comics, reverse this running right to left. Both otherwise follow most of the same basic rules beyond that mirroring. We read Comics One Panel at a time–analogous to one word at a time–to the end of each row of panels–analogous to a sentence. And then back to the left [or right for manga] to start over.

From left to right, top row first and then back and from left to right again. So in this nine panel page layout example, the arrows show how we’d read it. -Salgood Sam

This is why almost nobody can do this work successfully. This very simple page is nine different drawings where the character has to be consistent, the art has to be crisp, the eye line has to be right, the angles have to be dynamic and the page design has to flow.

Or look at this page from a random Flash issue.

That’s 12 different panels that all have to work together with the rest of the book to make something that feels cohesive.

You can’t just hire an illustrator to make this because it takes the combination of a hundred skills at once and then, on top of that, it has to tell a story.

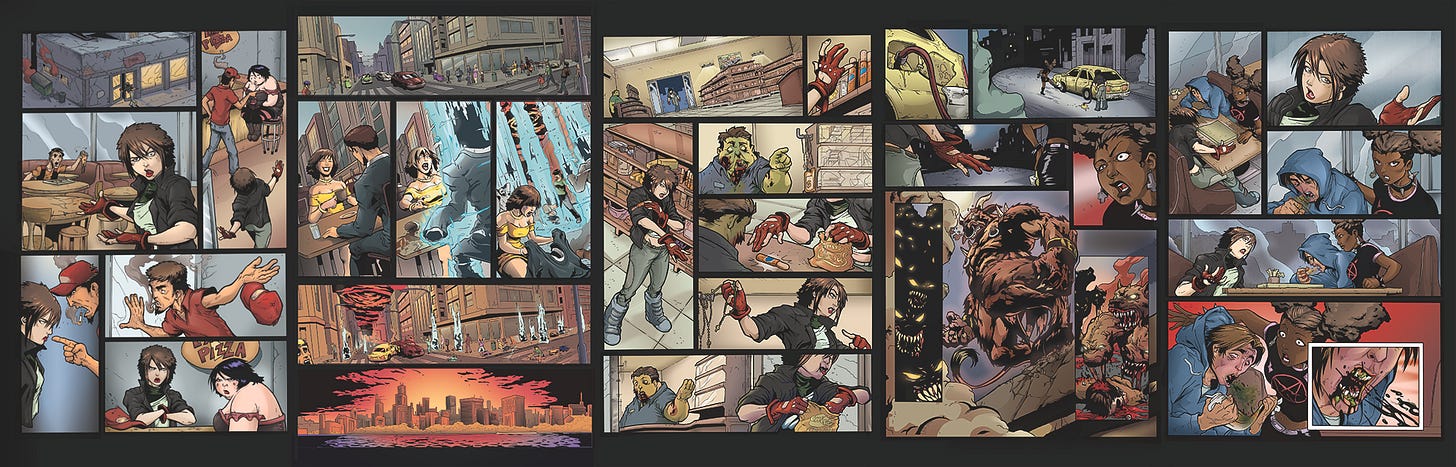

Because that’s another thing…comic artists have to be incredible storytellers, too, because they have to take this hot mess of words…

…and turn it into this beautiful final page.

How even do they take those jumble of words and turn it into a cohesive story? If you aren’t a comic book artist, how would you even know about panel design or page design? It’s not one of your core skill sets because you don’t have to do it on a regular basis.

So, how do you find a comic artist? Well, you can join some Facebook or Reddit groups, but you must ask if they have done sequential work. If they cannot produce at least three 4-5 page sequential pages (that means in order that tell a story) of a comic, then you should not work with them. Sequential means in a sequence, not a random collection of cool-looking pages.

As the name alludes to, sequential art refers to the use of visuals – such as drawings, images and/or photos – that are used in a sequence in order to tell or illustrate a story. In some cases, it includes a combination of visuals and text thought text is not necessary for it to be considered sequential art. -Pulse College

I’m harping on this, but sequential does not mean “a page of comics”. Comic artists who have never done a comic will try to send you random pages that look cool, but you’re trying to see if they can tell a story. This is a sequence of sequential stories from Katrina Hates the Dead.

Do you see how this tells a story? It shows the artist can turn words into art that makes sense as a story. Now, look at these random pages from the same issue.

Do you see how while these pages are nice, they don’t actually tell you anything about the artist’s storytelling ability? This is why you need sequential pages.

Otherwise, the best thing to do is either go into a comic shop and find some comics, or visit conventions and take to artists directly. Something that gets on the comic rack at a local store will likely be of a quality and has successfully completed production. Just like editors, comic book artists are mostly freelance and often available for work at rates you wouldn’t believe….because comics pay like doo doo.

How to pay a comics artist?

One of the easiest ways to lose your shirt in comics is to pay an artist upfront for a whole comic, especially if they don’t already know how (and still want) to draw comics. If you hire an editor and/or use my strategies above for finding an artist, you likely won’t get fleeced, but artists have a tendency to wait until the money runs out to finish jobs, even if they have every intention of doing the work.

I have found the best way to make it fair is to pay an advance of $500-$1000 to the artist upon commencement, and then pay every 5-10 pages of completed work. This keeps the artist motivated and prevents you from getting royally screwed.

Here’s the thing, though. You have to pay on time and in the correct amount. Don’t mess around. Put it on a credit card if you have to, but always pay on time and in the correct amount. Always.

Because here’s the rub…while you’re in production comic artists have all the power. The further you get in a book, the more power they have because readers hate seeing art change in the middle of a story arc.

A Story Arc is typically one or more consecutive comic book issues which define a story with a beginning, middle and end. One or more Story Arcs may or may not make up a Storyline. -Marvel Database

In general, a story arc is 3-6 issues of comics (and publishers generally don’t want to commit beyond that for indie comics anyway).

For your first story, I highly recommend looking at something much shorter than a whole story arc. Try to work with artists on one-shot stories, or even an anthology piece.

In comics, a one-shot is a work composed of a single standalone issue or chapter, contrasting a limited series or ongoing series, which are composed of multiple issues or chapters. One-shots date back to the early 19th century, published in newspapers, and today may be in the form of single published comic books, parts of comic magazines/anthologies or published online in websites. In the marketing industry, some one-shots are used as promotion tools that tie in with existing productions, movies, video games or television shows. -Marvel Database

I recommend a one-shot story of 20-48 pages to prove you can complete a comic and that you like working with an artist.

I prefer working with artists on a 4-8 page anthology story before committing to working with them further. This is how comics publishers have found new talent for generations and I have found it very helpful in scouting potential collaborators.

An Anthology Comic is a comic containing multiple stories, often by different writers and artists. The different stories may or may not all be set in the same 'verse. Some have art and writing house styles of various strengths.

Anthology comics used to be common in America, but are less visible nowadays. Marvel and DC, originally published several stories in one issue of their respective comics; only the most popular characters ever got a whole issue devoted to them, and even then it was typically a group of shorter stories about the character. Nowadays, Marvel and DC typically publish one or two stories per issue of each comic — the Decompressed Comic and Writing for the Trade pretty much forced the end of the anthology at the Big Two. However, Marvel has recently attempted to revive the anthology format with Marvel Comics Presents; the first series lasted 175 issues but the second only 12. They've since tried giving it another go, this time re-using the Strange Tales title. A more successful attempt has been Marvel's Voices, a set of themed anthologies, each one published annually, timed to coincide with events such as Pride Month and Black History Month.

It is also easier to find independent comics that go down the anthology route.

In Britain, anthologies are the norm. Most are aimed at pre-teen children and consist primarily of a set of one-to-two page gag strips, though there are exceptions. If a comic is successful, a publisher may print a summer special, featuring longer stories which often revolve around some theme. Very successful comics may even have annuals printed. An annual, as its name suggests, is a hardback collection of new stories published once a year, typically just before Christmas. These stories tend to be considerably longer than those in the main comic, and the annual also often has things like quizzes, activities, and text stories.

If a certain character proves to be very popular, they may get their very own comic. This may be either a one-off or semi-regular extended story, or it may be a full-blown Spin-Off. Judge Dredd is a good example - although, in typical British style, the spin-off Judge Dredd Megazine is itself an anthology. -TV Tropes

Mistake #3: They don’t understand the comic book production process

Just because you might understand the book production process doesn’t mean you understand anything about comics. Most writers think because they have written a couple of books they are experts on all aspects of publishing, but comics are a whole different medium. A good editor is as much a production manager as a creative partner. This is generally how the process looks, though your process will likely look different than this one.

Scripting - Just like with books, a comic starts with a script, except when it starts with thumbnails from an artist, but seeing as you probably aren’t an artist if you got this far, it’s safe to assume you will start with a script.

Editing - Once you have a script, it will go to your editor, who will help you polish it up. Then, they will discuss artists with you. If you’ve been working with your editor for a while already, you have probably discussed artists. They may have even gone out to recruit a few already or at least to get quotes from them. This is also when you will decide on the tone and art style of the book to give it the best chance for success. Different art styles are associated with different types of books. My book Pixie Dust has been seriously hamstrung because it looks like a YA book, but it is quite gory, limiting the target audience. I love it to pieces but the wrong people pick it up more often than not, and it’s not something a simple recover or proofread can fix.

Testing - Ha! You thought I was going to go right to production, didn’t you? No, now we have to test the artists and make sure they are right for your book. If you’ve already worked with an artist, or they have an extensive catalog, you can go straight into contracting, but usually, you’ll have to spend some time testing to make sure you and the artist and on the same page. This process can take forever, but if you don’t find the right artist, then your book will suffer. So, take your time and don’t cut corners. One of the main questions you’ll have to answer in this process is whether you’ll be hiring one artist for each step of the process or a single artist to complete every stage/multiple stages.

Character design - Once you have the right artist, you can move to character designs. They will likely have designs for the main characters, and the overall feel of the story, from testing with you, but this is when you nail down all the other characters. These are all character designs Renzo Podesta did for our book Ichabod Jones: Monster Hunter.

Sketches - From here, you move on to sketches of each page. These are very loose thumbnails of what the page design will look like. Honestly, I can never tell what’s going on with sketches, and they are normally so sloppy that I just ask them to give me loose pencils, but some artists give sketches that are very good and even make sense. Here are legible sketches from pages 1 and 2 of Ichabod Jones: Monster Hunter, issue #5.

Pencils/inks - These are often two different processes, but digital art has allowed them to be combined depending on the artist. In general, I like to hire one artist to get me through at least the ink stage, and then hire a colorist and letterer as necessary. However, hiring a different penciler and inker can be a good idea depending on the vibe you are going for in your book. Additionally, hiring a single artist will be cheaper but take more time than having different artists for each stage of the process. Here is how Renzo moved from sketches to inks for a few of the panels he sketched above.

Colors - You will be surprised how much of the art comes alive in the coloring stage. If you are going to put out black-and-white comics, this process is called shading or grayscaling. However, I highly recommend color comics, even though they are more expensive and limit the printing options, because they are considerably more marketable. Notice below how much detail has been added in the coloring stage of these panels.

Lettering - Please hire a great letterer. The single biggest mistake people make in the production process is to hire a substandard letterer. Lettering destroys good books and degrades great books. This is the last stage of the art production process, but it’s also one of the most critical. Great lettering can save a book as often as bad lettering can kill it. Notice below how the lettering enhances the art from above.

Prepress - This is the process of compiling the book for printing, making sure your files are in the right color space, and doing final checks with proofreaders to make sure you didn’t make any mistakes. Here is how to book looks when it’s done.

There are so many more stages in comics than in novels, and at each one it’s critical you hire a professional to make sure you don’t destroy your book. Additionally, it’s important to know your end goal because you can’t go back and change it once the art is complete.

Mistake #4: They don’t read the contract

I have already written about this extensively here, but you have to read the contract before you sign anything, especially with a publisher.

One of the biggest mistakes young writers make is getting into a terrible contract they can never leave. I’ve dealt with this several times with books I want to publish. The creator sends me their original contract and THEY DON’T EVEN OWN THE RIGHTS.

That’s right. More than one person has sent me a contract in which they signed away the rights to their book for less than it cost them to make the book in the first place. It’s a brutal lesson, and I hate being the bearer of bad news, but I have to go back and tell them even they can’t do anything with the book because it’s not their property.

Imagine that. You have poured your blood, sweat, and tears into a book. You’ve paid for artists out of your own pocket. You’ve stayed up late nights toiling away to get the pages right. You were so excited to finally be able to get the book out there…and in doing so signed away the rights to the publishing company.

That’s bad enough, but what happens if that publisher sells their catalog to a company that sells the catalog to another company until that whole catalog of books is picked up by a conglomerate that sits on the books forever? This isn’t a fictitious tale. This actually happened to somebody I know.

If you haven’t read the article above, you absolutely should because it will give you a primer on what to ask your lawyer about before you sign. Also, always hire a lawyer to look over contracts. I am not a lawyer, so you can’t hire me or take my advice as anything but my opinion.

Mistake #5: They try to make a 1:1 translation

Novels are a written word medium and comics are a visual medium. One of the biggest ego hits authors take is that people buy comics for the artwork. They stay for the story, but buy for the art.

Because of this, and it should go without saying, but the same things that work in novels don’t work in comics, and vice versa.

The differences are subtle but important. Prose can capture motion and invisible, inward sensations without much trouble, but in a comic every sensation must be communicated visually, each action broken down into a series of still images. We cannot see someone’s heart skip a beat, or their throat close up, so as descriptors, these are not terribly useful in a comic book script. Instead, a writer must find outward, visual ways to describe those same feelings. Maybe the character’s jaw drops; maybe they press one hand to their chest. Maybe there is a beat between two actions: a repeated panel without dialogue to show a character hesitate or startle, freezing in place before they react to something. A comic book script operates from a kind of extreme third-person POV: every emotion, even the most subtle, must be visible. This doesn’t mean every emotion must be visible on the face—some of the most brilliantly executed scenes in comics occur with a POV character’s back to the reader, or a juxtaposition between narrative captions and facial expressions that tell you someone on the page is lying. Yet even when this is the case, the choice of what to reveal and what to conceal is made using images. You must show because you cannot tell.

It can be tempting, in such a scenario, to make the dialogue do most of the heavy lifting, but dialogue takes up valuable real estate on the page, covering up the artists’ work, so even it must be made as economical as possible. I flinch now when I see giant paragraphs crowded into speech balloons in some of my early stuff, and today I have a rule: if a chunk of dialogue is longer than two typed lines, it needs to be broken up into several balloons, or even better, edited down until it does fit into two typed lines. -G. Willow Wilson

For instance, in the novel, Magic, Ollie can see through illusions to a monster’s true essence, but it didn’t make sense to make a big deal about it in the text. When we did the comic, Black Market Heroine, we decided to make the monster characters apparent to the readers from the jump. Comics is a visual medium and thus the monsters jumped off the page.

Additionally, while verbal jokes and puns work great in novels, sight gags work way better in comics.

Some jokes work in both, like when Anjelica hands Ollie a pen to use as a wand.

But you’re missing a huge opportunity to lean into what works in the comic medium by trying to do a straight adaptation. Those kinds of adaptations almost never work. Plus, it’s way more fun to gleefully play in a new medium and use new tricks to do things that don’t work in novels.

Additionally, it makes your writing better overall and teaches you tricks you can bring to all your writing.

Well, it won’t come as much of a surprise to hear that graphic novels are a visual medium and as such lend themselves to stories in which visuals play an important role. They are like movies in this way. Yes, it is possible to make a super-talky movie like My Dinner with Andre, but most movies are naturally filled with treats for the eyes. When I first got my start in comics, the visuals often drove the storytelling quite literally. I’d think, “Wouldn’t it be cool to draw a castle that had come to life?” And I would proceed to concoct a sequence that allowed me to do just that…

…I especially love creating dialogue scenes in comics, as this is where the move from words to pictures is at its most rapid fire. A three-panel sequence could go like this:

A man asks a question. You read the speech bubble but also glance at the facial expression to interpret his mood. He appears confident. Maybe a little mischievous.

In the next panel you see the other character—a woman—react. There is no speech bubble, forcing you to study her facial expression: She seems startled by the question.

In the next panel, you see that same character, but with her facial expression having changed to anger. She lays the man low with a devastating comeback.

In just three panels, your brain has leapt between words and pictures several times. If a silent film asked you to keep jumping back and forth between reading words and watching actors gesture at each other, it would soon become irritating. In comics, the comparable experience is delightful and so natural as to become almost unnoticeable. It’s like the pages are teaching your brain to dance, and before you know it, your brain is jitterbugging and moving around like Fred Astaire. -Mark Crilley

That is the magic of comics.

BONUS: Authors don’t understand how to make money in comics

I’m not sure anyone really knows how to make money in comics, but I’ve managed to work in comics for close to 15 years without going bankrupt and this is what I’ve found; the magic, secret sauce for making money in comics.

Make a comic issue for a reasonable price, which is probably less than $3,000/issue, but definitely less than $5,000/issue. You might need to cut the page count to make it work, but I have found that 20-page issues work well for me. I also work in a more cartoony style, which makes my art costs cheaper than a more realistic style.

Make sure your finished story arcs are no more than 150 pages at the end of the day. I tend to make my comics somewhere either 96 or 112 pages so that they line up with a book signature for a comic, which is usually 16 pages.

Invest in the production of two issues before you launch your first Kickstarter. Expect to spend another $2,000 on printing and shipping after your campaign ends.

Now you need to do some sort of preorder campaign to raise the funds for those books. Kickstarter is my preferred platform because it’s where most of the comics industry hangs out. You’ll likely want at least 2-4 variant covers for your launch. It’s a good idea to hire some known artists with decent-sized followings for these covers, as they will likely bring some buyers to your campaign.

With a good campaign, you can expect to raise $2,500-$5,000 on issue one, and another $2,500-$5,000+ on issue two. Use that money to pay for the rest of your arc, launching each issue one at a time and including previous issues as backer rewards. If you do this right, you will either break even on all costs of production before you launch the trade paperback campaign or come close. You can also exhibit at conventions, but you will likely not make much money until you have the trade on the table. That said, if you already have a novel, then it might make sense for you.

Now, you have 100-150 pages of art that are completely paid for by your previous campaigns, or close to it, you run another Kickstarter campaign for the trade, which will net you the most money (Since you've built your audience with single issues) and it will be all profit after you pay print costs.

Then, rinse and repeat. I have researched for hundreds of hours and spent 15 years working in comics. That's the only way I’ve found to make money in comics. That's how Marvel and DC have done it for years. That's how I do it. It's how it's done by almost anyone who wants to make money in comics.

The TL:DR version of this post (which I probably should have put at the top and not the bottom) is that if you want to make comics you should hire people who make comics. This might not seem like a huge revelation, but almost every author I talk to tries to work with artists and editors who don’t work in comics.

You would never hire a French translator who has never translated a book before, even if they speak French fluently. So, why would you hire an artist who has never made a comic before? Why would you hire an editor who doesn’t understand the comic workflow?

BTW: The opposite of this is true as well, I wouldn’t hire a comic artist to draw a book cover unless they had experience doing it. As a rule, you get the best results by hiring people who already do the work you want done.

If you don’t hire the right people, you’re going to have a bad time and you’re not setting yourself up for success. If you are interested in making a comic, I happen to keep a running list of recommendations on my website.

I also consult with authors one-on-one about comics and just about any other topic. You can book a time to talk with me here.

Finally, I have a comic book live on Kickstarter right now called Hospice: One Damned Good Thing. It’s a one-shot comic about a terminally ill prisoner who is sent to a hospice to live out his last days, only to find a horrible secret that threatens his very soul. It’s my first horror comic in years, and I love it so much. Hope you’ll check it out.

If you liked that article, please consider becoming a paid member. You can read almost all the comics I used in this article for free as a paid member, including Ichabod Jones: Monster Hunter, the seminal comics work of my career.

If you are a paid member, I recommend reading this article summarizing my best Kickstarter tips, this article about what to look for in a publishing contract, and this one about how to build a world-class network.

I also have a free podcast featuring interviews with comic creators David Pepose, Marv Wolfman, Jim Zub, Ben Templesmith, and Pat Shand, comic book publishers Michael Son and Barbra Dillon, and Margot Atwell, previous Director of Comics and Publishing at Kickstarter.

If you are not a paid member, you can read everything with a 7-day free trial, or give us a one-time tip.

Thank you- knowing this stuff will help me when the time comes to bring my characters and stories to the world of comics.